Read more

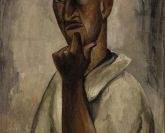

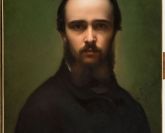

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Portrait of a Capuchin Friar, 1838

Oil on canvas

90 x 72 cm

Signed and dated bottom right: Granet. pinxit. / 1838

Inscriptions on the spines of the books: histoire / sacrÉ [sic] ; vies des / saints.

Literature

Unpublished.

-490x700.jpg)

Granet holds a special place among French landscape painters of the early 19th century. Unlike his contemporaries Bidauld, Boguet, Chauvin and Denis, he did not follow the classical tradition as revived by Valenciennes, but developed his own direct, intuitive way of translating and synthesising nature – one which heralded Corot’s modernity. Admitted to the free drawing school at Aix in around 1788-1789, Granet studied Constantin’s workshop he became friends with Auguste de Forbin, a young nobleman whose career became closely linked to his. He went to Paris with Forbin in 1796 and joined David’s studio two years later. It was also through Forbin that Granet became linked with the Lyonnais artists Révoil and Richard, which led to his being associated with the “artistocratic” section of the studio by Delécluze, who wrote about it in his memoirs. Unable to pay for his lessons, Granet pursued his training independently by studying the old masters in the Louvre; it was not long before he was an exhibitor there himself, taking part in the 1799 Salon, the beginning of his career as an exhibition artist.

In 1802, he embarked on the journey to Italy with Forbin, and settled in Rome, where he discovered the fountainhead of his art as well as a wide network in the French community. At the Salon, to which he regularly sent works, his originality was recognized thanks to his “interiors”. In 1806 Chaussard praised this artist “who had created a genre of his own and developed his talent while following in nobody’s footsteps nor adopting the style of any school.” Stella dans sa prison (Moscow, Pushkin Museum), which was acquired by Empress Josephine at the Salon of 1810, brought him considerable fame; it reached its peak with Le Choeur des Capucins (New York, Metropolitan Museum), a work that was so much in demand after its presentation in Rome in 1815 that Granet produced no fewer than twelve versions for the most prestigious collections. The Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy was responsible for the success of that painting, which exalted the spiritual life and the rites of a community outlawed by the Napoleonic Empire in Rome. At the end of July 1824, not without regret, Granet left the Eternal City and returned permanently to Paris, where he became curator of pictures in the Royal Museums, a post which Forbin, who was now the director, had obtained for him.

Granet was not a portraitist. The rare faces that appear in his work were those of his female partners, or his own, painted from time to time over the course of his life, and with the same economy of means. Dated 1838, the portrait of a Capuchin friar is therefore all the more surprising. Its interest lies less in its austere, to say the least, picturesque charm than in the new aspect that it brings to our knowledge of the artist. While the identity of the sitter is

unknown, the portrait is certainly proof of Granet’s enduring attachment to the Friars Minor Capuchin, who were associated with his celebrity and who had only recently regained their legal right to practise in France, having been subject to the revolutionary laws outlawing religious congregations, which continued until the beginning of the July Monarchy. Rendered with a marked concern for truth, the grave physiognomy of the venerable old man almost acquires the value of a vanitas, particularly when one considers the psychological mood of the painter during the year 1838, when the afflictions of age had inclined him towards “moral tepidness” and “despondent melancholy”.1

(M.K., trad. J.H.)

1. Letters from Forbin to Granet on 20 May and 14 August 1838, in Isabelle Neto (ed.), Granet et son entourage. Correspondance de 1804 à 1849, Nogent-le-Roi, 1995, pp. 186, 191.

Shorten

Read more

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

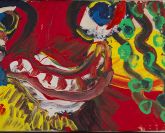

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

-165x133.jpg) Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

-165x133.jpg) Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

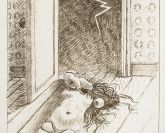

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

-165x133.jpg) Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

-165x133.jpg) Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

-165x133.jpg) Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

-165x133.jpg) Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

-165x133.jpg) Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

-165x133.jpg) Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

Élisabeth Sonrel

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)